The Association of Greek Art Historians organized a seminar by James M. Saslow on Friday, March 9, 2018 at the Amphitheater of the Benaki Museum, 138 Pireos Street, Athens, Greece.

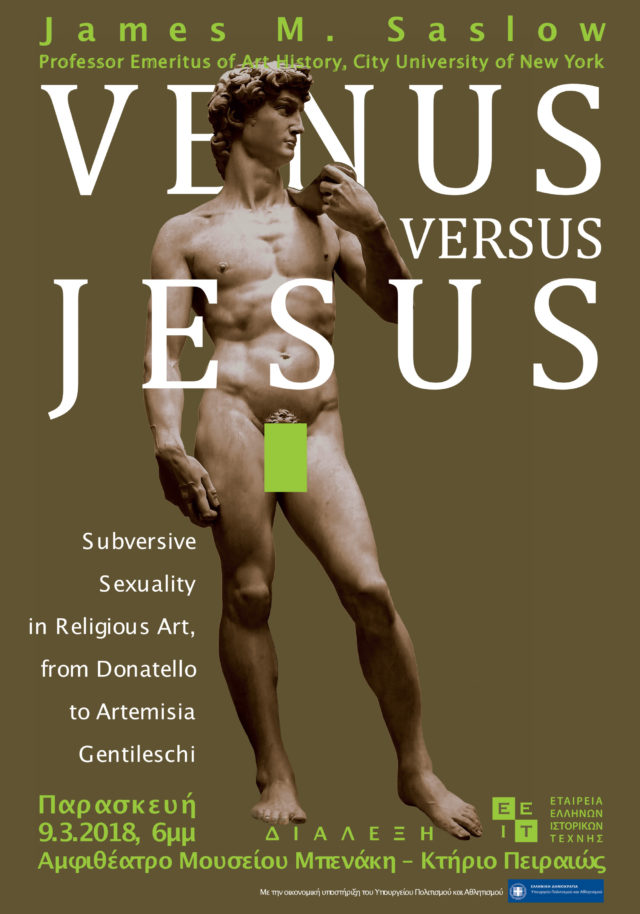

The seminar was entitled “Venus versus Jesus: Subversive Sexuality in Religious Art, from Donatello to Artemisia Gentileschi” and addressed the following topics:

Renaissance and Baroque artists frequently inserted beautiful bodies, both male and female, into religious images. Beginning with Donatello’s bronze David, sacred figures often appear idealized and nude or suggestively draped, communicating a passion that is as much earthly as heavenly. Sometimes their “sex appeal” is appropriate to the sacred message, but other images arouse physical desires that were excessive or forbidden. This lecture traces the shifting fortunes of eros in art through three phases. From Donatello to Michelangelo, the Catholic Church exploited erotic appeal in order to attract the viewer, but the Counter-Reformation turned against such “lascivious” imagery in the mid-sixteenth century, only to favor it again in the seventeenth.

The crucial problem was that religious art needed the physical body, because only supreme beauty could inspire passionate spiritual reverence toward sacred figures, but images of beauty also had the power to excite sinful earthly temptations. Some artists inadvertently went too far in an orthodox direction, while others deliberately introduced forbidden eroticism, particularly between men. The Council of Trent set out to purge religious imagery of these problematic trends in the 1540s, introducing strict rules of decorum, subject matter, and censorship.

After 1600, the Church again sought to arouse piety through physical beauty and passionate emotions, but some artists still crossed the line into forbidden excitement. At this time, too, the first generations of women artists began to reinterpret biblical narratives from a female viewpoint; Artemisia Gentileschi, for example, subverted the tradition of women as beautiful, passive objects by emphasizing her protagonists’ own active subjectivity. The shifting ambivalence toward the erotic in sacred art symptomized a central conflict in Renaissance culture between Christian and pagan-secular values, between Hebrew and Hellene, particularly in matters of sexual morality.

James M. Saslow is Professor Emeritus of Art History and Renaissance Studies at Queens College and the Graduate Center of the City University of New York.

He previously taught at Columbia University, where he received his PhD in 1983; at Vassar College; and as Kennedy Visiting Professor in Renaissance Studies at Smith College. He focuses on the Italian Renaissance and Baroque period, with special interests in gender and sexuality, global exchange, and the visual aspects of theater. His first book, Ganymede in the Renaissance (Yale, 1986), helped open art history to the role of homosexuality and gender in early modern art and society. A co-founder of the Center for Lesbian and Gay Studies at CUNY and former co-chair of the College Art Association’s Queer Caucus, he has lectured internationally, particularly on Michelangelo, whose poetry he translated (1991). Saslow specializes further in early modern theatrical design; he has created costumes and backdrops for a Baroque opera and wrote and directed a stage adaptation of Castiglione’s Renaissance classic, The Book of the Courtier. While a Mills Fellow at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, he completed The Medici Wedding of 1589, named best book of the year by the Renaissance Society of America in 1997.

The seminar was open to the public and was part of the Series of Lectures by Distinguished Art Historians organized by EEIT. It was delivered in English.